It’s been several months, readers! I apologize. It’s been a wild ride.

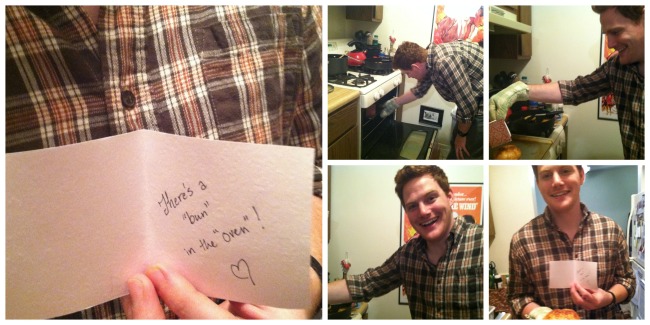

And really, it’s funny that my last post in September was about a DIY facial; the breakout I experienced at that time was due to a rush of progesterone, which was one of many biological clues (and one prove-it-all test) that led to this announcement to Boaz:

Can you read it? The moment was captured live on September 17 on my smartphone, so it’s a bit blurry at this size. My message next to the sticky bun says, “There’s a ‘bun’ in the ‘oven’!”

I’ve confided on this blog before that I (hence, we) have been using the Fertility Awareness Method for nearly two years – first, to avoid pregnancy naturally (successfully, too), and then, more recently in August, to reverse the pregnancy-avoidance method to attempt to conceive. I don’t know why I was so convinced that it would take us months and months to conceive on any method, but I was pretty darn wrong.

So, the last few months, I’ve been busy, busy, busy, in addition to being sleepy, nauseous, and hungry, to the point of coming home from work and making dinner, eating it, and falling asleep in my plate instead of writing blog posts.

The second trimester is definitely here now, though, so I’m feeling much more like myself . . .

. . . And at the same time, not myself. Because at the moment, I’m essentially two people in one body.

What a strange way to start off 2015.

As weird a body-space as I’m occupying now, the head-space of this change in state has been even stranger. Everyone has heard stories about the bizareness of pregnancy dreams and cravings and so forth, but no one warns you about the philosophical space you enter.

One of the more persistent thoughts I’ve had as I entered 2015 has been this:

I’m a soul, nurturing another soul. Whoa.

It’s thought-fodder enough to really shape my resolution this year:

I want to learn how to feed my soul so that I can ultimately nurture my child’s.

That gets into some tricky grounding, though. After all, what even is a soul? And why is it that nobody (not even in most churches, folks!) seems to ever talk about it, or seem care about it anymore?

We live in an era of history where the shape of the body and the accomplishments of the mind are EVERYTHING. Our society chases new fitness and diet regimes, running until we have to replace our knees, then spend tens of thousands on degrees to prove we know what we know in the hopes of getting hired, making money, and enjoying life.

But we forget that neither the body nor the mind (or the material gains we make from them) are guaranteed to last – just ask anyone in a hospital spending what thousands of dollars they once had in savings on cancer treatments, or chat up one of the pleasantly confused old citizens wandering around your local nursing home.

I want to give myself, and my child, the only kind of health and wealth that lasts beyond this life.

So, in this post, I want to begin exploring what a soul is, and what a healthy versus an unhealthy soul does. There’s a lot of (older) literature written about the soul, and there’s a lot to pull out of it in an attempt to define something so ineffable. Please feel free to jump in with your own gleanings from what you’ve read and discovered!

Defining the “Soul”

When most of us think of the word soul, the mostly widely-recognized early Western-world definition of the soul springs to mind without our realizing it, simply because this early definition defined so much of our foundational thinkers’ philosophies. Rendered in Greek as ψυχή, or psychē, it is loosely translated as the “life, spirit, consciousness,” closely related to the verb for breathing or blowing, essential for life; more recently in human history, it has served as our root for the word psychology (the study of the soul). We owe the popularity of this root word to Plato’s Republic, in which Plato presents the soul in three parts: logos (logic, mind), thymos (emotion, spiritedness, our response to the action in our world, considered masculine) and eros (the desires and wishes, considered feminine), which all strive to rule the will of a person. In Plato’s view, in a balanced, spiritually healthy person, logos rules the other two elements, and so commands the psyche. Like his teacher, Socrates, Plato believed that the soul, though influencing the physical body, survived after death, unlike the physical body.

In Hebrew tradition, the word for the soul is nephesh, likewise meaning “vital breath,” and, similar to Plato’s view, is an entity somewhat distinct from the body, although it nevertheless imbues life to the physical form on Earth through the touch of the divine.

Due to Septuagint-based translations of the Hebrew scriptures, many Christians pass over the word nephesh without even realizing that it refers to the soul when they read the English versions of Genesis 2:7 (“The Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being [or soul, since this is nephesh].”), and the Psalms (such as Psalm 49:8, often translated as “The ransom for a life (nephesh) is costly; no payment is ever enough.”), and even the Torah-building law book of Deuteronomy (in Deut. 4:9a, the English Standard Version translates most correctly, “Only take care, and keep your soul (nephesh) diligently.”)

Other times, the Septuagint renders nephesh directly into the English word soul or spirit, most notably in the Psalms, which depict some behaviors of the soul: yearning for the divine (and in many places, responding to the sublime as a connection to the divine), feeling unrest, and enjoying celebratory praise and giving blessing, as well as enduring beyond life, leaving behind an empty body. Here are some examples:

Psalm 43:5a: “Why, my soul, are you downcast? Why so disturbed within me?”

Psalm 63:1: “O God, you are my God; earnestly I seek you; my soul thirsts for you; my flesh faints for you, as in a dry and weary land where there is no water.”

Psalm 103:1: “Bless the LORD, O my soul, and all that is within me, bless his holy name!”

Psalm 116:7: “Return to your rest, my soul, for the LORD has been good to you.”

Psalm 146:4: “When their spirit (here, denoted as ruach, meaning “breath, wind, spirit”) departs, they return to the ground; on that very day their plans come to nothing.”

This last Psalm uses the word ruach, which also has a few other instances of use in the Old Testament canon, including uses that tell us more about the soul or spirit. I’ll summarize what I found: A person’s “spirit” has many characteristics, including unfaithfulness (Psalm 78:8), sincerity (Psalm 32:2), and humility (Isaiah 57:15). The “spirit” can also be unsettled, even crushed (Joshua 5:1), but it can also be restored and brought back to health (Isaiah 57:15).

In the Christian New Testament, the word psyche (sometimes rendered psuche) is predominantly used for the soul (this is presumably Koine Greek rather than Plato’s Classical Greek). Jesus’ teachings frequently mention the word, and it’s re-emphasized again in the apostolic writings. All these instances agree that the soul is eternal, valuable, and able to be damaged by darker forces and burdened by evil doings (this is remarkably similar to ancient Egyptian beliefs recorded in the Book of the Dead, by the by).

Here are just a few example verses:

Matthew 16: 26 –[Jesus speaking:] “For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul (psyche)? Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?”

Matthew 10:28- [Jesus speaking:] “Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul (psuche). Rather, be afraid of the One who can destroy both soul and body in Hell.”

1 Thessalonians 5:23 – [Paul writes:] “May God himself, the God of peace, sanctify you through and through. May your whole spirit, soul* (psuche) and body be kept blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

All of this is some heavy theology. But the point is pretty clear. The soul is important. We should care about it. But how do we figure out how to do that? Maybe it’s best to look at what the unhealthy soul and the healthy soul look like for some clues.

What a soul so often lacks is the quiet needed for clarity. We live in a noisy, attention-seeking world.

How an Unhealthy Soul Behaves

“Because my inner life is invisible, it is easy to neglect.” – John Ortberg

The soul seems to be a fragile thing in scripture and even in Platonic philosophy. Since it serves as the harbor for the complexity of our personal traits, spiritual energy, and competing desires as well as acting as the burden-bearer of our life experiences, it is prone to great unrest.

Theologian Dallas Willard devoted a great portion of his life to understanding the behaviors of the soul; one of his students, John Ortberg, boiled down some of the behavioral patterns of souls in poor health using one of the parables of Jesus from Matthew 13: 3-9, the Parable of the Sower (Ortberg, 54-60). This parable outlines three unfulfilling attitudes of various “states of soil” (which the reader understands as representing the states of various people’s souls) as they respond to a generously given “seed” (a message from God or the divine):

Hardened: This is a soil (soul) that has surrounded itself with a protective shell of bitter cynicism or suspicion after bearing the burdens of a life made difficult through sources of continual, overwhelming fear. Good things that try to grow here never even get the chance to take root.

Shallow: This is a soil (soul) that has a very shallow level of growthful depth, caused by a preoccupation with immediate gratification and comfort that leaves no room for “staying power” or capacity for commitment beyond that initial gratification. This is a soil that won’t give the best of itself to nurture anything. What good things try to grow here unfortunately die quickly.

Thorny/Cluttered: This is a soil (soul) whose focus is entangled with externals that seem important – the pursuit of a material lifestyle, awesome reputation, or unique and exciting experiences— that choke out its desires for the more valuable, simple, less glamorous blessings that come from the divine. Good things that try to grow in this soil have to constantly compete and do battle with the myriad pleasures and status-boosters that this soul desires.

Sad thing is, none of us choose to have souls in these conditions, but they do happen—to all of us, I think, just at various times of life. And when they do, they alter our psychological (our psyche’s) mindset completely, blinding us to the deeper truth of our circumstances. It can lead to our isolation or alienation from friends, cause rifts in relationships, or set us up for disappointment and heartache in other ways. Often, we look back on these periods of poor soul-health later in life with regret, recognizing at last the many missed opportunities or the time-wasting pursuits (or even relationships!) that we were too blind to see for what they really were while we were rolling around in our bad soul-dirt.

I’d love to try to protect myself in the future from having more of those regrets, and teach my child to keep him or herself balanced to avoid these spiritual pitfalls . . . but life, it seems, can really throw us all for a loop.

How a Healthy Soul Behaves

“A soul,” explains John Ortberg in Soul Keeping, “is what integrates your will (your intentions), your mind (your thoughts and feelings, your values and conscience) and your body (your face, body language, and actions) into a single life. A soul is healthy – well-ordered – when there is harmony between these three entities and God’s intent for all creation. When you are connected with God and other people in life, you have a healthy soul” (43).

Keeping this in mind, there are a few specific ways that a healthy soul then behaves:

A Healthy Soul Stays in Alignment with What It Values.

I think it’s hard to feel settled within ourselves when we observe occasional hypocrisy in our own behavior. Worse, inconsistency within our actions can become even a little pathological, leading to disordered thinking and behavior over time. But when our souls are consistently aligned with what we most deeply value, we gain a deep spiritual contentment and true sense of being where we are meant to be. One of the prayers I’ve learned at my job at a Jesuit high school comes from Fr. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., and it goes like this,

“Nothing is more practical than

finding God, than

falling in Love

in a quite absolute, final way.

What you are in love with,

what seizes your imagination,

will affect everything.

It will decide

what will get you out of bed in the morning,

what you do with your evenings,

how you spend your weekends,

what you read,

whom you know,

what breaks your heart,

and what amazes you with joy and gratitude.

Fall in Love,

stay in love,

and it will decide everything.”

This kind of empowering commitment gets our butts off the couch and out there with other people who need us. It’s a powerful, meaningful way to live and to see life.

A Healthy Soul Finds Contentment.

. . . But not by going out the door looking for something/someone to give it contentment, but by practicing the art of gratitude for what is already present.

How often do we forget how blessed we truly are? Friends, family, even our abilities, all of it is really a gift. We forget that, sometimes! But when we remember to be grateful, we no longer feel the need to go restlessly searching on, seeking that one other thing we need to make us happy. We find happiness in the moment.

We remember, too, that God is a part of that happiness, when we see how little of what we had was actually earned by our actions. “Praise the Lord, my soul,” writes the Psalmist in Psalm 103, “and forget not all His benefits . . . who redeems your life from the pit and crowns you with love and compassion, who satisfies your desires with good things . . .”

A Healthy Soul Draws Sustenance from Something Other than the Self.

We live in an age where even well-meaning people say, “Take care of yourself!” when we feel run-down or are faced with a difficult trial. While it’s sensible to care for our bodies with adequate rest and nourishment, a soul finds its sustenance beyond the bounds of our bed and board, and certainly finds better food for growth and thought when we aren’t too focused on ourselves.

When we’re run down by the demands of our draining, self-filled lives, our souls miss the replenishing focus and direction provided by the divine. We often forget the power of prayer in this regard, but as Francois Fenelon, an erstwhile royal tutor to King Louis XIV (who fell out of favor when he stood up to the monarch) discovered while in a very stressful exile, “In order to make your prayer life more profitable, it would be well from the beginning to picture yourself as a poor, naked, miserable wretch, perishing of hunger. . . These are true pictures of our condition before God . . . and God alone can heal you” (qtd. Ortberg, 87).

A Healthy Soul Has No Need to Become Anything Else.

A balanced, well-nourished soul that is connected to others, content with its own resources, and is connected to God is virtually unstoppable. It gives the soul-bearer an oddly glowing, resilient, hard-to-drag-down quality, even in tough times. It also grants the soul-bearer the kind of un-self-concerned freedom, inner strength, and courage that’s needed to reach out to others in need in ways that are deeply meaningful and life-changing. There is a ton of value in having a soul that’s in this state, because this in itself is extraordinary in terms of its spiritual potential.

In the words of Dallas Willard, “You are an unceasing spiritual being with an eternal destiny in God’s great universe . . . The most important thing in your life is not what you do; it’s who you become. That’s what you will take into eternity.”

But of course, getting to this point can really take some work. Join me in the coming weeks as I come around to this topic again in a mini-series of posts called “Workouts for the Soul.”

In the meantime, happy, soul-nurturing New Year to you all!

Ruth

NOTES:

* There are some disagreements about the role of the soul versus the spirit among Christian theologians; some view them as interchangeable, as “spirit” (rendered pneúma or ruach in Greek ) closely resembles the meaning of nephesh in Hebrew (both referring to breath, as in breath of life of the divine). But there’s also a lot out there about whether the soul and the spirit are separate entities, as it appears sometimes that they are used interchangeably, and at times, as separate and defined entities.

My take on this debate rests on Hebrews 4:12, “For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, bone and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart.” From this metaphoric phrasing I (admittedly simplistically) extract that soul and spirit are loosely both a part of the same spiritual force, although with defined functions, like a bone contains marrow, with the ossified tissue of bone playing a different, but supporting role to marrow tissue. To me, though, this whole argument really isn’t terribly important; regardless of the roles of each, both spirit and soul point to the deepest, most essential and spiritually-enduring parts of us.

Non-linkable Citation:

Ortberg, John. Soul Keeping: Caring for the Most Important Part of You. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014. Print.